Vivaldi in Venice

Overview of the study day

Antonio Vivaldi – the last of the great Venetian writers – is arguably the one Baroque composer whose music is a direct reflection of the city in which it was composed. Listen to a Vivaldi concerto and hey presto you are transported directly to the heart of 18th century Venice.

Antonio Vivaldi – the last of the great Venetian writers – is arguably the one Baroque composer whose music is a direct reflection of the city in which it was composed. Listen to a Vivaldi concerto and hey presto you are transported directly to the heart of 18th century Venice.

The reasons for this are many. First, Vivaldi was a son of Venice and had an inate understanding of Venice’s unique aesthetic, which included a passion for colour, spectacle and display of emotion, points that are reflected time and time again in his music. Second, Venice solved its problems with abandoned and orphaned children in a altruistic manner and the way in which that was done impacted on Vivaldi as a composer, teacher and musical director. Third, Vivaldi’s health problems and his eccentricities as a man and a priest dictated his path as a musician and performer in Venice’s cultural life.

Against the luxurious backdrop of 18th century Venice, and with live musical performances, this study day explores the amazing world of Vivaldi’s music – music that is as intrinsically Venetian as the canvasses of Canaletto.

Sample timetable with content

10.30-11.30 – Session 1

The Relationship of Vivaldi to Venice

The day opens with an introduction to the city of Venice, and explores what it is that has made Venice unique among European urbanizations. It examines Venice’s great love of ritual and spectacle and how this in turn is reflected in the music of Vivaldi – particularly in his concertos. It also looks at how Venice managed to redefine itself after its decline in the 17th and 18th centuries and how the music of Vivaldi and his contemporaries was designed to reflect Venice’s Indian summer of newfound confidence and brilliance.

11.30-11.45 – Break

11.45-1.00 – Session 2

The Ospedali

The second lecture examines the role of the Ospedali in the social and musical world of Venice. It looks, particularly, at the Pietà and Mendicanti institutions – with which both Vivaldi and his father had strong musical connections – and will show a wide range of documents, manuscripts and paintings that throw light on this very important area of Venetian charity and culture. It also examines some of the concertos that Vivaldi wrote for the pupils at the institutions to reveal the very high level of technique demanded of them in order to play the works.

1.00-2.15 – Lunch

2.15-3.30 – Session 3

Vivaldi’s Impact on His Contemporaries

The final session takes a look at the impact of Vivaldi’s musical style on the music of his Venetian contemporaries, as well as on the music of JS Bach, GF Handel, M Corrette and J Stanley.

Some of the themes appearing in the study day

The Venetian Concerto

Throughout its history, show and spectacle have been central to the image that the Venetians have projected to rest of the world. Whether this was a dignified procession from the Doge’s palace to the basilica, or the annual Marriage with the Sea, when the Doge cast a gold ring into the lagoon as a sign of true and perpetual dominion over the Adriatic (see below). These events have all helped to give Venice a sense of theatre, showmanship and drama.

Rituals of state reached their height during Vivaldi’s lifetime, when Venice consciously changed its identity from being a powerful force on the stage of European politics and international trade and commerce, to being a tourist attraction and a place of entertainment – a role that it has upheld to this day.

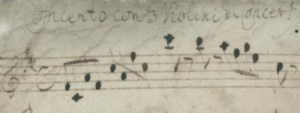

In the musical world of Venice, there is a particular form that may be said to parallel the phenomena of show and spectacle: the

In the musical world of Venice, there is a particular form that may be said to parallel the phenomena of show and spectacle: the  concerto – a form that even today is designed to entertain, to move, to amaze, and above all, to impress. Vivaldi is particularly remembered for the writing of concertos (some 600 in all), in fact, it could be argued that Vivaldi is the inventor of the concerto, as we might know it today. In other words, a musical form that is designed to show off the skills of a soloist – or soloists – who are placed against the backdrop of an accompanying orchestra.

concerto – a form that even today is designed to entertain, to move, to amaze, and above all, to impress. Vivaldi is particularly remembered for the writing of concertos (some 600 in all), in fact, it could be argued that Vivaldi is the inventor of the concerto, as we might know it today. In other words, a musical form that is designed to show off the skills of a soloist – or soloists – who are placed against the backdrop of an accompanying orchestra.

The Ospedali

In order to understand Vivaldi and his relationship to the concerto – and therefore to Venice – the role of the four Ospedali needs to be considered. The Ospedali  were charitable institutions for orphans and abandoned children, especially girls. Originally, these foundations were designed as ‘hotels’ for crusaders, but as the crusades abated, their function was changed into charitable foundations (orphanages), and became famous for their high grade level of tuition, and more important, for their high grade level of music making.

were charitable institutions for orphans and abandoned children, especially girls. Originally, these foundations were designed as ‘hotels’ for crusaders, but as the crusades abated, their function was changed into charitable foundations (orphanages), and became famous for their high grade level of tuition, and more important, for their high grade level of music making.

The four Venetian Ospedali attracted a wide range of high grade music teachers, for example after his arrival in Venice in 1670, Giovanni Legrenzi took a position as music teacher at the Ospedale Santa Maria dei Derelitti, remaining there until 1676. While in 1740, composer and harpsichordist Baldessare Galuppi was appointed director of music at the Ospedale dei Mendicanti.

The Ospedale della Pietà was the foundation with which Vivaldi had a lifetime connection (1703 -1739) and it was for them that the bulk of his concertos and religious music was written. The musical standard reached in the Pietà Chapel – and those of the other Ospedali – was so great, that large congregations were attracted to them in order to hear the choirs and instrumentalists perform, especially in Lent, when music in other churches tended to be less elaborate.

Edward Wright writing in the 1720s remarked:

Every Sunday and holiday there is a performance of music in the chapels of these hospitals, vocal and instrumental, performed by the young women of the place, who are set in a gallery above and, though not professed, are hid from any distinct view of those below by a lattice of ironwork. The organ parts, as well as those of the other instruments are all performed by the young women. They have a eunuch for their master and he composes most of their music. Their performance is surprisingly good … and this is all the more amusing since their persons are concealed from view.’

Every Sunday and holiday there is a performance of music in the chapels of these hospitals, vocal and instrumental, performed by the young women of the place, who are set in a gallery above and, though not professed, are hid from any distinct view of those below by a lattice of ironwork. The organ parts, as well as those of the other instruments are all performed by the young women. They have a eunuch for their master and he composes most of their music. Their performance is surprisingly good … and this is all the more amusing since their persons are concealed from view.’

The public wanted to hear the girls play concertos, the girls needed concertos to play, and Vivaldi found employment by writing concertos. The writing of concertos, coupled with Vivaldi’s great skills as a violinist, made him become one of the greatest concerto writers of all time.

Venice and colour

Colour, is something that you can find everywhere in Venice, whether it is used in the decoration that can be seen on the west end of St Mark’s Basilica (below),

or whether it is the famous glass that is produced on the island of Murano, or even the highly decorated posters that advertise the carnival each year.

In the world of art, the Venetian painters were famous for their use of colour; and one of the most celebrated colourists of all time was Paolo Veronese, based in Venice, and his Wedding at Cana shows his skill in this direction to an astonishing degree (see below right).

This passion for – and use of – colour may in part reflect the ready availability of high quality pigments such as ultramarine, made from the semi-precious stone lapis lazuli imported from Afghanistan. And this, joined with the fact that canvas, the fabric of ship sails, was more popular as a support for paintings in Venice than anywhere else and may have stimulated a preference for the bold, highly visible, expressive brushwork that is such a distinctive feature of Venetian painting.

It could be argued then, that the long tradition Venice had for trading over seas, as well as its importance as a seafaring port, may well have had a direct influence on this aspect of the arts. This is cause and effect.

Turning now to music, I can think of no other Baroque composer who could be said to have more ‘colour’ in his music than Vivaldi. And by colour, I don’t just mean the subtleties of harmonic and rhythmic textures that lie in his compositions, but the highly imaginative scoring of his concertos and religious music. In other words, his choice of musical instruments for a particular work in question.

Vivaldi used a greater range of instruments in his music than any other composer that I know of during this period, and the range of instruments in turn reflects the variety of instruments played by the young girls at the Ospedale della Pietà: mandoline, tromba marina, recorders, bassoon, clarinet, trumpet, lute, horn etc

![The Scotish [sic] Gigg](https://petermedhurst.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Peter120813untitled-shoot-2.jpg)