Henry Purcell – ‘Fairest Isle’ – sung and played by Peter Medhurst

__________________________________

Despite his early death, Henry Purcell (1659-95) remains one of the finest musical figures of the late Baroque era, an all round English composer who wrote in a wide variety of musical forms ranging from tiny 16-bar harpsichord pieces to large scale works for the court and the theatre.

The study day looks closely at Purcell’s music to see exactly what it is that gave him his unique and distinctive musical voice. It also compares his style with that of contemporary musical wizards on the Continent, and goes on to assess the impact that Purcell had on later generations of composers, including Handel, Haydn, Tippett and Britten.

The study day looks closely at Purcell’s music to see exactly what it is that gave him his unique and distinctive musical voice. It also compares his style with that of contemporary musical wizards on the Continent, and goes on to assess the impact that Purcell had on later generations of composers, including Handel, Haydn, Tippett and Britten.

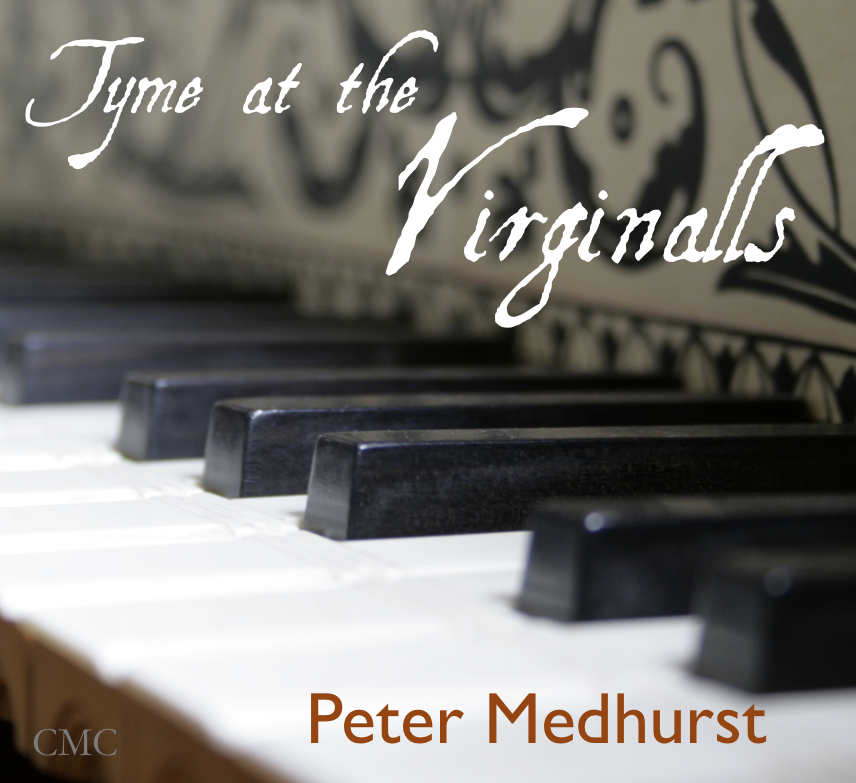

There will also be a chance to sample some of Purcell’s songs and harpsichord works, which Peter Medhurst will perform live during the event. Music includes Prelude from Suite No 2 in G minor, Rondo from Abdelazar, Sweeter than Roses, Lord what is Man?, Crown the Altar, She Loves and She Confesses too, A New Ground, Suite in C major.

If the budget will allow, the event may be enhanced by an additional singer or instrumentalist. And for a real taste of the period, a 17th century style harpsichord after Andreas Ruckers may also be factored in, at a modest cost.

__________________________________

Henry Purcell: Prelude for harpsichord (Suite No 2 in G minor) – played by Peter Medhurst

Suggested timetable for the day

10.30-11.30 Session 1

The world of Henry Purcell – his family, his career, his output, his publications, his contemporaries, his early death

11.30-11.45 Break

11.45-13.00 Session 2

What is it that makes Henry Purcell’s music sound like Henry Purcell? Peter Medhurst discusses Purcell’s style and shows the points that make his music great and individual; he also looks at the impact that Purcell’s music had on later generations of composers

13.00-14.15 Lunch

14.15-15.30 Session 3

A live recital of vocal and keyboard music, which will include highlights from Purcell’s repertoire, as well as music by his contemporaries, including John Blow, Jeremiah Clarke, Pelham Humfrey and William Croft

The study day is illustrated throughout with digital images and live music examples

__________________________________

Introducing Henry Purcell

It is interesting to notice how many great composers in the history of music managed to be born – or die – on 22nd November, the feast day of St Cecilia, the patron saint of music.

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, the second child and eldest son of Johann Sebastian Bach was born on 22nd November 1710; Conradin Kreutzer or Kreuzer the German composer and conductor was also born on that day in 1780, as was Joaquín Rodrigo Vidre (1901) and Benjamin Britten (1913). By contrast, Arthur Sullivan died on the Patroness’s day in 1900.

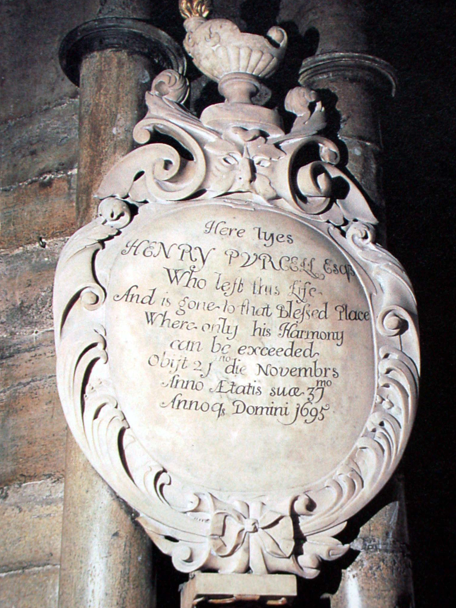

It would be wondrously satisfying if Purcell had accomplished a similar feat, especially since he had written so many superb odes to celebrate St Cecilia’s day (he was actually the first composer to do so), but the date on his memorial plaque – appropriately near the organ – in Westminster Abbey, relates unequivocally, that Purcell died on 21st November 1695, thus missing the feast of the saint by one day.

It would be wondrously satisfying if Purcell had accomplished a similar feat, especially since he had written so many superb odes to celebrate St Cecilia’s day (he was actually the first composer to do so), but the date on his memorial plaque – appropriately near the organ – in Westminster Abbey, relates unequivocally, that Purcell died on 21st November 1695, thus missing the feast of the saint by one day.

No matter, if Purcell failed to mark the 22nd November with either his birth or his death, his music is no less great; a fact that is born out by the many tributes made to him in verse and music by his colleagues and close friends, following his early death at the age of 36. As his contemporary Thomas Tudway remarked I knew him perfectly well. He had a most commendable ambition of exceeding every one of his time, and he succeeded in it without contradiction, there being none in England, nor anywhere else that I know of, that could come into competition with him for compositions of all kinds.

Compared with Handel, who follows him as the next big figure in the chronology of English music, Purcell is a seemingly shadowy figure, with comparatively few personal anecdotes and virtually no surviving memorabilia.

The portrait (right) of Purcell by – or after – John Closterman dates from the last year of the composer’s life, and with its marked Classical manner, consciously projects the image of a latter day Orpheus – quite literally Orpheus Britannicus. All that is missing is the Thracian lyre. So, all thanks must be given to the artist Closterman that we do at least have an impression of the composer, albeit a stylised one. However, this one portrait – from which others were derived – shows a mannered figure, far removed from the tremendous vibrancy, breadth, and sheer down to earth aspect, of Purcell’s extraordinary music.

The portrait (right) of Purcell by – or after – John Closterman dates from the last year of the composer’s life, and with its marked Classical manner, consciously projects the image of a latter day Orpheus – quite literally Orpheus Britannicus. All that is missing is the Thracian lyre. So, all thanks must be given to the artist Closterman that we do at least have an impression of the composer, albeit a stylised one. However, this one portrait – from which others were derived – shows a mannered figure, far removed from the tremendous vibrancy, breadth, and sheer down to earth aspect, of Purcell’s extraordinary music.

This shadowy aspect of Purcell even spills over into the very pronunciation of his name. Should it be spoken as Purcell with the accent on the second syllable, or should it be pronounced Purcell, with the stress on the first? I have a suspicion that this ghost can be laid easily to rest by looking at a passage in Dryden’s An Ode, on the Death of Mr Henry Purcell. In it, is a phrase that without question places the stress on the first part of Purcell’s name

This shadowy aspect of Purcell even spills over into the very pronunciation of his name. Should it be spoken as Purcell with the accent on the second syllable, or should it be pronounced Purcell, with the stress on the first? I have a suspicion that this ghost can be laid easily to rest by looking at a passage in Dryden’s An Ode, on the Death of Mr Henry Purcell. In it, is a phrase that without question places the stress on the first part of Purcell’s name

So ceas’d the rival Crew when Purcell came,

They Sung no more, or only Sung his Fame.

John Blow, who sets the Ode to music, follows suit with Dryden’s accent, and since Purcell was well known to these men, it would appear logical that even in poetry and music, they would utilise the correct pronunciation. To my mind, Dryden and Blow qualify the pronunciation, once and for all.

__________________________________

![The Scotish [sic] Gigg](https://petermedhurst.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Peter120813untitled-shoot-2.jpg)