In the Wake of Handel

The impact of Handel on 300 years of British Music making

300 years of British music making

Lecture description

Despite his German birth and his Italian musical training, Handel remains one of the most important composers that England ever nurtured. Not only did his music have direct influence on his musical contemporaries, but his larger-than-life personality had a profound effect on the literary, visual and decorative arts as well – both in his lifetime and after his death, in 1759.

By exploring the works of the French sculptor Roubiliac, the paintings of Hudson and Denner, the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, the novels of Samuel Butler, the Crystal Palace, the chimes of Westminster, as well as compositions by Sullivan and Tippett, the lecture assesses the cultural influences Handel had on a nation, as he once wrote from whom I have receiv’d so Generous a protection.

Music performed may include: Handel in the Strand – P Grainger, Tune Your Harps from Esther – GF Handel, My Voice Shalt Thou Hear Betimes, O Lord – J Corfe, This Helmet I Suppose was Meant to Ward off Blows from Princess Ida – AS Sullivan

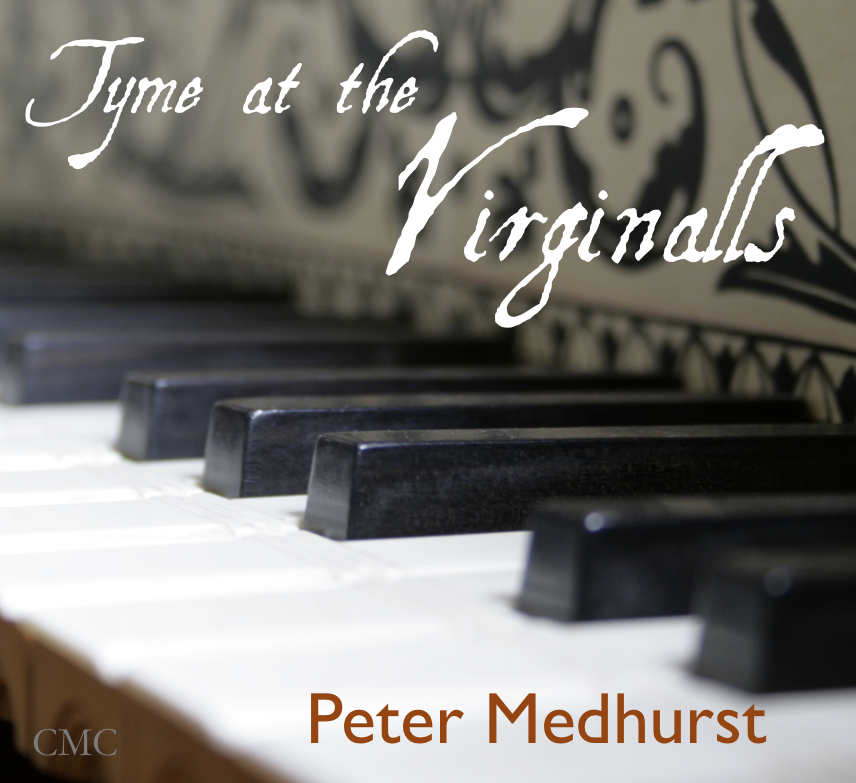

Handel – Courante from Suite No 5 in E for Harpsichord – played by Peter Medhurst on a copy of a Pascal Taskin instrument of 1769

Introduction

Arguably the most famous piece of keyboard music that Handel ever composed is the Theme and Variations known as The Harmonious Blacksmith, which constitutes the last movement of the Suite in E major from Suites de Pieces pour le Clavecin, published in 1720. Here is the opening:

Handel’s Harmonious Blacksmith theme played by Peter Medhurst

Years later, in 1912, Percy Grainger came along, and inspired by the famous set of Variations wrote his Handel in the Strand, basing his musical ideas on the harmonies that underpin the opening bars of Handel’s theme. He went on to say

my dear friend William Gair Rathbone (to whom the piece is dedicated) suggested the title “Handel in the Strand,” because the music seemed to reflect both Handel and English musical comedy (the “Strand” — a street in London — is the home of London musical comedy) — as if jovial old Handel were careering down the Strand to the strains of modern English popular music. . . . . I have made use of matter from some variations of mine on Handel’s “Harmonious Blacksmith” tune.

Whether Grainger has been successful or not, in conjuring up a 20th century Handel, I’ll leave for you to judge; but for generations of listeners to the BBC’s Light Programme in the last century, one thing was certain: Handel in the Strand had a quintessentially English ring to it, and took its place very easily among the light Radio classics of the 40s and 50s.

‘Quintessentially English’, is a term that I would also use to describe the music of Handel; which is curious, because like Percy Grainger who was Australian born, Handel wasn’t a native of Britain either, but hailed from Saxony, in Eastern Germany. Yet from the moment that Handel arrived in England, as a young man of 25, until his death in 1759 – just over 250 years ago – he devoted his energies as a musician and a composer, to entertaining the London audiences of the day; and became so bound up with this, that he – and his music – constitute a vital part of the cultural development of this country, both during his lifetime, and after it.

Not only did his music have direct influence on his musical contemporaries, but his larger-than-life personality had a profound effect on the literary, visual and decorative arts as well. By exploring the works of the French sculptor Roubiliac, the paintings of Hudson and Denner, the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, the novels of Samuel Butler, the Crystal Palace, the chimes of Westminster, as well as compositions by Sullivan and Tippett, the lecture assesses the cultural influences Handel had on a nation, as he once wrote from whom I have receiv’d so Generous a protection.

Reading list

Handel | Christopher Hogwood – Thames & Hudson

Handel – the man & his music | Jonathan Keates – Gollancz Paperbacks

![The Scotish [sic] Gigg](https://petermedhurst.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Peter120813untitled-shoot-2.jpg)